Young Keene Man Remembered as " Pure Soul," A Teacher Who Left A Legacy Of Lessons

By Paul Miller, Executive Editor, Keene Sentinel, November 2, 2014

It is the arbitrary nature of death that confounds us. Its unpredictability is, in a sense, one of the great mysteries of our existence.

And so we accept it as part of our reality, because we have no choice, and we do our best to make sense of why things happen the way that they do, and when.

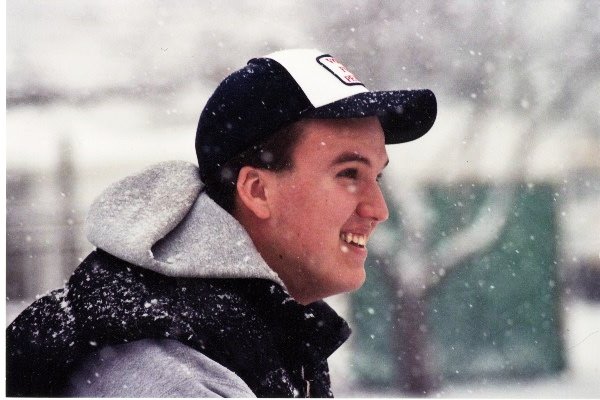

Brandon Russell, a Keene native, died last week. He was 27 years old. He was still beaming from having found his dream job as an elementary school teacher more than two years ago. Brandon — “Bran” to those who knew him best — beamed all of the time. It was his distinguishing and enduring feature. That and his smile; his big heart; his friendship, his nurturing way; his goofy, quirky side; his wisdom; his earnestness; his loyalty and his intellect.

At a Keene bagel shop just a little more than a week ago, before heading out of town to join his students, Brandon told me his 5th-grade class was “the best class” he could imagine and that his school in Grafton, Vt., was a “perfect fit.” Work was a highlight of his day; he lived for his students. He couldn’t be happier, he told me.

Brandon was a special person. I so enjoyed running into him. I relished those times, and though our conversations were mostly brief, Brandon was the type of person you could chat to about life for hours.

If you met him once, you were not likely to forget him. Brandon lived in colorful and positive tones — and attire. He didn’t have a filter; he didn’t need one. He was happy by nature and it was no coincidence that his flight path veered naturally from trouble and turbulence.

“He always knew what to say to make you feel better,” his younger brother, Nick Dwyer, 19, said Friday. “But it was more than that; he genuinely wanted you to feel better. He would take your pain if he could.”

Brandon died Wednesday at his Keene home, from a pulmonary embolism brought on by a blood clot in his leg.

He had always been a person mature beyond his years — something his parents, his teachers and his friends all spotted — but he was just finding his stride in the real world, his influence as a teacher barely underway.

It is not the quality of Brandon as a person — good people die every day — but the timing of his passing, perhaps, that mystifies us and causes us to ask “why?”

The weight of the news of Brandon’s death tugged on my heart like a small anchor. I asked “why?” many times.

Then I met his family: Nick, a college sophomore; Tammy Dwyer, his mother; Tad Dwyer, his stepfather; Morgan Mason, his girlfriend; and John White, Tammy's uncle.

For a few hours Friday in the family living room, we shared stories about Brandon; we laughed and we cried, and amid the emotion of it all the picture of a remarkable young man who had given so much and still had more to offer emerged, like a pencil etching that gained color and clarity with each shared memory.

Brandon was not a perfect person, Tad assured, but he was far from ordinary, too, his family agreed. He was unique; he had difference-making qualities; he had a teacher’s DNA, no doubt; and he had a measured temperament that adults envied.

He had a special talent, too, for helping others to solve an issue or to arrive at an answer without providing it, Tammy said. “He’d lead you there and guide you, and you’d figure it out. That was also the teacher in him.”

Brandon was also a fierce and notorious gamer. You might stand a chance of beating him at Trivial Pursuit, at “Jeopardy!” or at the poker table, but it was a slim chance at best; more often you were bait.

“Getting him enthused about anything, especially a game, was never an issue,” said Tad, who came into Brandon’s life when Brandon was 3 years old. “Homework for him was as much fun as anything else. He loved an intellectual challenge. He’d play a game for the game’s sake, but he loved to beat me, too.”

Brandon’s father, Dan Russell, said he will remember most his son’s “overall character” and that he was “someone who brought joy and happiness to anyone whose life he touched.

“There will never be another Brandon,” Dan said.

I met Brandon about a decade ago, when I was a coach at Keene High School and he was a student.

I always thought of him as a person who came into this world like a shooting star, with grace and force, as if he had been somewhere or had seen something that no one else had. To his view, all things and all people were inherently good. His optimism grabbed you and made you feel immediately better. He was incessantly curious.

Katie (Breit) Bjerke discovered that presence in middle school, where she and Brandon first met. They became close friends. Bjerke lives in New Jersey now, but she and Brandon maintained a close friendship. Bjerke recalled how, in high school, during one particularly long winter and in “freezing” Keene High classrooms, Brandon regularly offered her his football sweatshirt to stay warm. “It happened about every day,” she said, “and eventually he just gave me the sweatshirt. I still have it.”

She also has a blanket, made from sweatshirt material and bearing the colors and logo of Brandon’s college, Keene State, that he sent to her when she was in college, too. “He was so thoughtful to do that; and then to think, he gave me the shirt off his back, literally,” Bjerke said.

Brandon never took himself too seriously, another theme that surfaced while reminiscing. He embraced the term “big goofball,” and even had it on his license plate. Well, “goofbal,” which was the closest spelling available.

Brandon did things on a whim. On “pajama day” at the school where he first taught, he wore a full-body Snuggie fleece; he entered a snowshoe race out of shape and with no snowshoeing experience and posted a proud, smiling, next-to-last finish; and he taught himself to knit, but his first project, intended to be a scarf, became a 20-foot-long blanket. “He figured it out (the knitting part), he just didn’t know how to stop it and so the scarf became a blanket,” Tad said, laughing. “This huge blanket.”

At 6-foot-3 and more than 200 pounds, Brandon was well-suited for football, which he played at Keene High. But he was third string and rarely saw action. Still, the game fit his interpretation of life more generally, in that it allowed him to make more friends. So when the team’s final game was over, “he bawled,” Tammy said. Size-wise, he was regarded more as a big teddy bear than a menacing football lineman.

Tammy said a summer tutoring session with Donna Fairbanks, a Keene Middle School teacher, to help Brandon prepare for an advanced-level 7th-grade math program in the fall, convinced Brandon that he wanted to be a teacher. “She changed his life, obviously,” Tammy said of Fairbanks. “That relationship changed him, and they stayed friends,” Tad said. “Brandon would regularly come back to the school, and to Keene High School, as a touchstone.”

Tammy said her oldest son was born happy. “He slept through the night on his second night at home,” she said. “He’d stand up in his crib, looking out and holding on, and he’d always be smiling. He never cried. To say that he was an easy child is an understatement.”

Tammy said she’s not sure what her days ahead will be like. Her family is tight-knit, she said. “A friend of mine used the word ‘amoeba.’ There are four of us, yes, but we don’t see one without seeing the others. As four we were like one; I don’t know yet how to be three.”

Nodding his head as if to agree, and speaking through soft tears, Nick said, “I don’t know if we’re ever going to laugh the way we once did, ever again. I will miss the energy Bran gave off. Every time I saw him he made me smile, without even trying.”

As for Tad, who credits Brandon for helping him to raise Nick, he said Brandon “kept me in check. I could talk to him as a son and as a colleague. He could talk about anything and he just kept adding to the repertoire. The maturity of our conversations just grew.

“He was the most fun-loving human, who had a serious side that allowed him to run a classroom.”

Morgan met Brandon through a friend at Keene State; they had been dating for about a year. She called herself the cynical one in the relationship, shrugging to acknowledge that that had to be the world’s worst-kept secret. “I’ll miss Brandon’s optimism and how much he balanced me out,” she said.

College roommate and friend Eric Laberge called Brandon “a pure soul, one of the few I’ve ever known. Some say people like Brandon are only in your life for a short window and their presence is meant to influence a lesson or change for the better. He will be sorely missed.”

I will miss Brandon for his friendly, approachable personality, and for his lessons on how to live a life of meaning, which he delivered not by lecture, but by example. And I will so miss his smile.

At the end of the day, two things mattered most to Brandon: family and friends. If you were part of that circle, you are forever blessed.

By Paul Miller, Executive Editor, Keene Sentinel, November 2, 2014

It is the arbitrary nature of death that confounds us. Its unpredictability is, in a sense, one of the great mysteries of our existence.

And so we accept it as part of our reality, because we have no choice, and we do our best to make sense of why things happen the way that they do, and when.

Brandon Russell, a Keene native, died last week. He was 27 years old. He was still beaming from having found his dream job as an elementary school teacher more than two years ago. Brandon — “Bran” to those who knew him best — beamed all of the time. It was his distinguishing and enduring feature. That and his smile; his big heart; his friendship, his nurturing way; his goofy, quirky side; his wisdom; his earnestness; his loyalty and his intellect.

At a Keene bagel shop just a little more than a week ago, before heading out of town to join his students, Brandon told me his 5th-grade class was “the best class” he could imagine and that his school in Grafton, Vt., was a “perfect fit.” Work was a highlight of his day; he lived for his students. He couldn’t be happier, he told me.

Brandon was a special person. I so enjoyed running into him. I relished those times, and though our conversations were mostly brief, Brandon was the type of person you could chat to about life for hours.

If you met him once, you were not likely to forget him. Brandon lived in colorful and positive tones — and attire. He didn’t have a filter; he didn’t need one. He was happy by nature and it was no coincidence that his flight path veered naturally from trouble and turbulence.

“He always knew what to say to make you feel better,” his younger brother, Nick Dwyer, 19, said Friday. “But it was more than that; he genuinely wanted you to feel better. He would take your pain if he could.”

Brandon died Wednesday at his Keene home, from a pulmonary embolism brought on by a blood clot in his leg.

He had always been a person mature beyond his years — something his parents, his teachers and his friends all spotted — but he was just finding his stride in the real world, his influence as a teacher barely underway.

It is not the quality of Brandon as a person — good people die every day — but the timing of his passing, perhaps, that mystifies us and causes us to ask “why?”

The weight of the news of Brandon’s death tugged on my heart like a small anchor. I asked “why?” many times.

Then I met his family: Nick, a college sophomore; Tammy Dwyer, his mother; Tad Dwyer, his stepfather; Morgan Mason, his girlfriend; and John White, Tammy's uncle.

For a few hours Friday in the family living room, we shared stories about Brandon; we laughed and we cried, and amid the emotion of it all the picture of a remarkable young man who had given so much and still had more to offer emerged, like a pencil etching that gained color and clarity with each shared memory.

Brandon was not a perfect person, Tad assured, but he was far from ordinary, too, his family agreed. He was unique; he had difference-making qualities; he had a teacher’s DNA, no doubt; and he had a measured temperament that adults envied.

He had a special talent, too, for helping others to solve an issue or to arrive at an answer without providing it, Tammy said. “He’d lead you there and guide you, and you’d figure it out. That was also the teacher in him.”

Brandon was also a fierce and notorious gamer. You might stand a chance of beating him at Trivial Pursuit, at “Jeopardy!” or at the poker table, but it was a slim chance at best; more often you were bait.

“Getting him enthused about anything, especially a game, was never an issue,” said Tad, who came into Brandon’s life when Brandon was 3 years old. “Homework for him was as much fun as anything else. He loved an intellectual challenge. He’d play a game for the game’s sake, but he loved to beat me, too.”

Brandon’s father, Dan Russell, said he will remember most his son’s “overall character” and that he was “someone who brought joy and happiness to anyone whose life he touched.

“There will never be another Brandon,” Dan said.

I met Brandon about a decade ago, when I was a coach at Keene High School and he was a student.

I always thought of him as a person who came into this world like a shooting star, with grace and force, as if he had been somewhere or had seen something that no one else had. To his view, all things and all people were inherently good. His optimism grabbed you and made you feel immediately better. He was incessantly curious.

Katie (Breit) Bjerke discovered that presence in middle school, where she and Brandon first met. They became close friends. Bjerke lives in New Jersey now, but she and Brandon maintained a close friendship. Bjerke recalled how, in high school, during one particularly long winter and in “freezing” Keene High classrooms, Brandon regularly offered her his football sweatshirt to stay warm. “It happened about every day,” she said, “and eventually he just gave me the sweatshirt. I still have it.”

She also has a blanket, made from sweatshirt material and bearing the colors and logo of Brandon’s college, Keene State, that he sent to her when she was in college, too. “He was so thoughtful to do that; and then to think, he gave me the shirt off his back, literally,” Bjerke said.

Brandon never took himself too seriously, another theme that surfaced while reminiscing. He embraced the term “big goofball,” and even had it on his license plate. Well, “goofbal,” which was the closest spelling available.

Brandon did things on a whim. On “pajama day” at the school where he first taught, he wore a full-body Snuggie fleece; he entered a snowshoe race out of shape and with no snowshoeing experience and posted a proud, smiling, next-to-last finish; and he taught himself to knit, but his first project, intended to be a scarf, became a 20-foot-long blanket. “He figured it out (the knitting part), he just didn’t know how to stop it and so the scarf became a blanket,” Tad said, laughing. “This huge blanket.”

At 6-foot-3 and more than 200 pounds, Brandon was well-suited for football, which he played at Keene High. But he was third string and rarely saw action. Still, the game fit his interpretation of life more generally, in that it allowed him to make more friends. So when the team’s final game was over, “he bawled,” Tammy said. Size-wise, he was regarded more as a big teddy bear than a menacing football lineman.

Tammy said a summer tutoring session with Donna Fairbanks, a Keene Middle School teacher, to help Brandon prepare for an advanced-level 7th-grade math program in the fall, convinced Brandon that he wanted to be a teacher. “She changed his life, obviously,” Tammy said of Fairbanks. “That relationship changed him, and they stayed friends,” Tad said. “Brandon would regularly come back to the school, and to Keene High School, as a touchstone.”

Tammy said her oldest son was born happy. “He slept through the night on his second night at home,” she said. “He’d stand up in his crib, looking out and holding on, and he’d always be smiling. He never cried. To say that he was an easy child is an understatement.”

Tammy said she’s not sure what her days ahead will be like. Her family is tight-knit, she said. “A friend of mine used the word ‘amoeba.’ There are four of us, yes, but we don’t see one without seeing the others. As four we were like one; I don’t know yet how to be three.”

Nodding his head as if to agree, and speaking through soft tears, Nick said, “I don’t know if we’re ever going to laugh the way we once did, ever again. I will miss the energy Bran gave off. Every time I saw him he made me smile, without even trying.”

As for Tad, who credits Brandon for helping him to raise Nick, he said Brandon “kept me in check. I could talk to him as a son and as a colleague. He could talk about anything and he just kept adding to the repertoire. The maturity of our conversations just grew.

“He was the most fun-loving human, who had a serious side that allowed him to run a classroom.”

Morgan met Brandon through a friend at Keene State; they had been dating for about a year. She called herself the cynical one in the relationship, shrugging to acknowledge that that had to be the world’s worst-kept secret. “I’ll miss Brandon’s optimism and how much he balanced me out,” she said.

College roommate and friend Eric Laberge called Brandon “a pure soul, one of the few I’ve ever known. Some say people like Brandon are only in your life for a short window and their presence is meant to influence a lesson or change for the better. He will be sorely missed.”

I will miss Brandon for his friendly, approachable personality, and for his lessons on how to live a life of meaning, which he delivered not by lecture, but by example. And I will so miss his smile.

At the end of the day, two things mattered most to Brandon: family and friends. If you were part of that circle, you are forever blessed.